A Few Words about Our Style and Approach

We need to say several things about how we will approach this subject.

1. We will briefly define negotiation. Negotiation is a form of decision making in which two or more parties talk with one another in an effort to resolve their opposing interests.

For most people, bargaining and negotiation mean the same thing, however, we will be quite distinctive in the way we use the two words.

2. Many people assume that the “heart of negotiation” is the give-and –take process used to reach an agreement. While that give-and –take process is extremely important , negotiation is a very comolex social process: many lf the most important factors that shape a negotiation result do not occur during the megotiation: they occur before the parties start to negotiate, or shape the context around the negotiation. The nature of nagotiation as a tool for agreement.

3. Our insinghts into negotiation are drawn from three sources.

3.1 Our Experience as negotiators ourselves and the rich number of negotiations that occur every day in our own lives and in the lives lf people around the world.

3.2 Source is the media – television, radio, newspaper, magazine, and Internet. The report on actual negotiations every day. We will use quotes and examples from the media to highlight key points, insights, and applications throughout the book.

3.3 Source is the wealth of social science research that has been conducted on numerous aspects of negotiation. This research has been conducted for more than 50 years in the fields of economics, psychology, political science, communication, labor relations, law, sociology, and anthropology.

When you shouldn’t Negotiate

When you’d lose the farm

If uou’re in a situation where you could lose everything, shoose other rather than negotiate.

When you’re sold out

When you’re running at capacity, don’t deal. Raise your prices instead.

When the demands are unethical

Don’t negotiate if your counterpart asks for something you cannot support be cause it’s illegal, unethical, or morally inappropriate – for example, either paying or accepthing a bribe. When your character or your reputation is compromised, you lose in the long run.

When you don’t care

If you have no stake in the outcome, don’t negotiate. You have everything to lose and nothing to gain.

When you don’t have time

When you’re pressed for time, you may choose not to negotiate. If the time pressure works against you, you’ll make mistakes, you give in too quickly, and you may fail to consider the implications of your concessions. When under the gun, you’ll settle for less than you could otherwise get.

When they act in bad faith.

Stop the negotiation when your counterpart shows signs of acting in bad faith. If you can’t trust their negotiating, you can’t their agreement. In this case negotiation is of little or no value. Stick to your guns and cover your position, or discredit them.

When waiting would improve your position.

Perhaps you’ll have a new technology available soon. Maybe your financial situation will improve. Another opportunity may present itself. If the odds are good that you’ll gain ground with a delay, wait.

When you’re not prepared

If you don’t prepare, you’ll think of all your bestquestions, responses, and concessions on the way home. Gathering your reconnaissance and rehearsing the negotation will pay off handsomely. If you’re not ready, just say “No”

Interdependence

One of the key characteristics of a negotiation situation is that the parties need each other in order to achieve their preferred objectives or outcomes. That is, either they must coordinate with each other to achieve their own objectives, or they choose to work together because the possible outcome is better than they can achieve by working on their own. When the parties depend on each other to achieve their own preferred outcome they are interdependent.

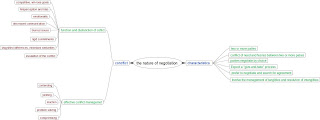

Conflict

A potential consequence of interdependent relationships is conflict. Conflict can result from the strongly divergent need of the two parties or from misperceptions and misunderstandings. Conflict can occur when the two parties are working toward the same goal and generally want the some outcome or when both parties want very different outcomes.

Definitions

Conflict may be defined as a “sharp disagreement or opposition, as of interests, ideas, etc” and includes “the perceived divergence of interest, or a belief that the parties’ current aspirations cannot be achieved simultaneously” Conflict results from “the interaction of interdependent people who perceived incompatible goals and interference from each other in achieving those goals.”